|

|

Post by stormberg on Apr 15, 2017 23:48:54 GMT -6

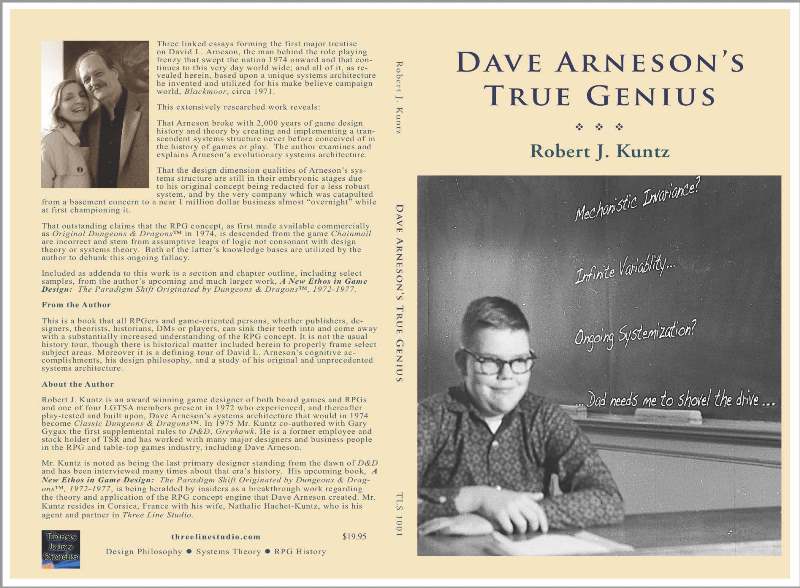

What is Dave Arneson’s True Genius?? Well... It kinda starts below...  ....and then by leaps and bounds... Breaks the sound barrier of game design history by 2,000 years... Join us in a giant step into the past that re-opens a future doorway David L. Arneson created and gifted to us! From the awarding-winning game designerand author Robert J. Kuntz:Dave Arneson’s True GeniusAvailable From Three Line Studio  |

|

|

|

Post by derv on Apr 30, 2017 18:35:30 GMT -6

Not much talk about this. Where's the buzz?

Well, I bought the book and want to share my thoughts. Here it goes.

Dave Arneson’s True Genius Initial Thoughts

Let me first start by saying that I am not a game designer. I am not a game historian. And I was not there when the roleplaying concept was conceived. These are some of the obstacles that, I feel, are unnecessarily put in the way of the reader through the writing of this text. These did not need to be obstacles. There was educational opportunity within the text to elucidate on all of these areas. Despite this, I do have some thoughts on all the above areas. So, what is to follow should be considered an opinion piece.

The book appears to be Kuntz’s attempt at reframing the context of the conversation in regard to the development of D&D and Arneson’s contributions using Systems Theory. In general, Game Theory is mostly concerned with mathematical predictability and strategy. It analyzes cause and effect. Kuntz mostly ignores this relationship. Instead of causality and catalysts, he prefers ideas of transcendence. What he actually seems to be suggesting is embodied in the methods of Metadesign, concepts that I would question were purposefully in practice during the development of D&D. Also, most of the language that involves System Thinking will very likely be lost on most. Maybe we are not the target audience? What I have found to be the simplest explanation is that System Thinking “attempts to illuminate how small catalytic events that are separated by distance and time can be the cause of significant changes in complex systems.” The book leads me to believe that Kuntz would not accept this definition. Yet, a system is composed of parts. It is not the “architecture” alone that makes up a holistic system. Kuntz rightly calls these parts sub-systems. Do not make the mistake of assuming that these sub-systems are inconsequential or insignificant. This is the impression that the book left me with. A system does require sub-systems and they are essential to it’s development.

As I presented above, Game Theory would support the vital nature of sub-systems and their causality to the end results. Keep this in mind when reading Kuntz’s essay on Chainmail and Braunstein. Their influences are in evidence in both the written text and playing of the game.

It is hard to embrace Kuntz’s suggestion that Historians need to be more engrossed with System Theory. If historians were to consider Game Theory, such things as the divergence from Arneson’s original design intents and the state of the current hobby could be attributed to Evolutionary Game Theory instead of simple economic motivations. Granted, it could be both. Despite what Kuntz suggests, History is also concerned with causality. At it’s most base form history is a linear presentation of such facts. Ideas occur in time and space. There is agency and efficacy considered.

For example, we have been taught that Edison invented the light bulb in 1879. Yet, would it have been possible without the contributions of Alessandro Volta, Humphrey Davy, Warren de la Rue, William Staite, Joseph Swan, Henry Woodward and Matthew Evans. The list could go further. It could move in the direction of glass, metals, electricity, and all the innovators that proceeded them. These developments were essential in understanding the history of the first commercial light bulbs development. Without this ongoing causality, it is questionable how or when this innovation would have existed. It is obvious to me how these parts (sub-systems) were built upon the concept (architecture) of the design to make it work. This may not be obvious to everyone.

Ultimately, it seems that those who are already inclined to adopt Kuntz’s ideas will easily do so. Those who look at this conversation from another angle and share a differing opinion to Kuntz’s view’s, will not be easily swayed by this text. Kuntz needs to find some common ground to start from if he is to change opinion. Honestly, I think more History would help his case.

|

|

|

|

Post by Fearghus on Apr 30, 2017 20:46:11 GMT -6

Haven't read it, but will try and get a copy. Glad you shared thoughts on the matter. I enjoy reading about RPG history, game theory, and game design.

|

|

|

|

Post by derv on May 1, 2017 15:38:37 GMT -6

If you enjoy game theory, I'd say the book is worth getting. It will at least get you thinking about the validity of it's lofty major point- essentially a complete paradigm shift in design. How Kuntz communicates how this was achieved is some of what I'm still chewing on.

One concept that I basically reject, that is associated with the roleplaying concept and seems to be in fashion among gamers lately, that Kuntz is also advocating, is what I like to call the Primordial Play Theory. I won't expound. You'll know it when you see it.

Also, Kuntz spends some time talking about open and closed systems. He categorizes Arneson's original concept (Blackmoor) and what became original D&D (Lake Geneva campaign) as open systems. He then goes on to explain how D&D became an increasingly closed system, starting with the advent of AD&D and it's insisted codification. He claims this was due to the desire to monetize the game. As I think about it, I truly think the ground work was already laid out with OD&D. OD&D was already emerging as a closed system through Lake Geneva's re-interpretations. I say this in relation to the alternative combat system that is claimed everyone used, the use of experience points and their application to class advancement, that was said to be painstakingly play tested, with railing against excessive level gains in other quarters expressed by Gygax in the zines, and how gold garnered, in and of itself, became a primary means of acquiring xp. This is in contrast to Arneson who required gold to be spent. These are but a few elements of the original published game that became increasingly codified and not easily modified without altering other elements (sub systems) of the game. What happened was it went from suggestions to requirements. Yet, Arneson's examples given in the FFC did not contain such parameters. It was clear you needed to fill in the gaps and that he was giving examples of how it could be. He did not even include a combat system. Only passingly mentioning Chainmail. I do not get the same vibe from the LBB's. Though there is certainly a lot that you could choose to ignore or do different, I do not think the examples I gave above easily fall into that category. Yet, I am aware that there were growing campaigns at the time that did. Again, I do not get the impression that Gygax looked favorably on such modifications from some of the articles and editorials I've read.

I'd welcome hearing others impressions of the book and/or comments on the topic.

|

|

|

|

Post by cadriel on May 1, 2017 20:36:17 GMT -6

I read the book, and I don't want to reply on my blog because I am concerned that any opinions I register there will be received in the wrong tone. I'll put forward what at this point are some tentative notes about Rob's book.

First, the system theory concepts. I don't think that this is a useful way to look at roleplaying games. The entire book is written at a very high level of abstraction from what actually goes on at the table, and I am by nature more pragmatist than that. There are points where the level of abstraction gets so high that it's not clear what Rob is talking about, mostly in the second essay. I read the thing on Friday and still haven't figured out what the referent is for "This" in "This is what it is." Also, the list of design leaps that Rob puts forward in the first essay read like a description of roleplaying from some nightmare bureaucracy: "Ongoing applied design and design theory in real-time; embedded extensions of the design processing brought to bear in designing the game" is a monstrous assault upon the English language. So this makes me negatively disposed toward the book from pretty early on.

Second, I think he's remarkably unfair to Gary in talking about the shift from "open form" to "formula D&D." Yes, Gary said some regrettable things in Dragon magazine editorials in the '70s, but it feels unfair to re-litigate them when Gary embraced an open approach toward gaming late in his life. The whole first essay reads as negative on Gary, who was instrumental in making D&D a thing that could be run by people other than Dave Arneson.

Third, I'm not really sure this deserved to be its own book. There are too many references back to A New Ethos in Game Design, and the Arneson essays would have made a great deal more sense as an appendix to that book rather than publishing it without the larger work that it more or less requires to make sense, for instance, of the leaps that Kuntz lists in the first essay. It kind of felt like a very expensive advertisement for a later, forthcoming book.

Fourth, the whole derivation concept. I find the whole idea of "true designer" to put me in a bad mood, it's like talking about a "true Scotsman." I think that what was shown in Playing at the World and what we've learned since it was written shows that Blackmoor was a synthesis. It was a combination of a "dungeon Braunstein" and a Chainmail campaign. It added substantial innovations, but we see over and over in PatW that things like gaining levels and changing characters was not entirely new. Merely saying "no" to a bunch of design leaps is not proof that the game's main elements don't aren't an extension of Braunstein and Chainmail.

Finally, I found it to have no insight at all into Dave Arneson as a game designer. Because everything is in this heavy systems theory abstraction, there is no discussion of what Arneson actually did at the table that Kuntz thinks was brilliant. There's no discussion of what Dave's games were like or what they did that had never been done; indeed, there's really no sense of what Dave did aside from the systems theory descriptions which never give a really clear picure (by design).

So my thoughts are fairly harsh, and I don't want to do an in-depth review when it's clear that a lot of the leg work is in the larger book. But this one was a fairly big letdown for me.

|

|

|

|

Post by derv on May 2, 2017 1:20:09 GMT -6

cadriel, I think all your criticisms would be considered fair and worth a response from the author. I did not find them overly harsh. I see these sort of criticisms as expressions of frustration where the book failed to deliver on expectations. I hope Mr. Kuntz would view them likewise and not take them personal. I'll comment on them briefly. Your first comment is where I feel the book fails to educate and where it makes assumptions about the readers that may not be true. Otherwise, the target audience was actually intended for a more narrow audience than was marketed. More specifically, for designers and like minded. If a person is not of that bent, it is easy enough to get the feeling that the language purposefully obfuscates the subject. As for your second point, I am less affected. I think some valid criticism can be directed towards Gygax. Keep in mind that there was also a bit of do what I say and not as I do in how Gary played the game, from early on. But, I am inclined to think about Gary's contribution in a different light. The question I come to is, would D&D have been a marketable success without him? I'm inclined to say no, Arneson as true genius or not. Third, agree. Last points, yes I agree that Kuntz needed to rely more heavily on history to support his ideas.

|

|

|

|

Post by Stormcrow on May 2, 2017 8:05:58 GMT -6

But, I am inclined to think about Gary's contribution in a different light. The question I come to is, would D&D have been a marketable success without him? I'm inclined to say no, Arneson as true genius or not. The two questions are, would someone other than Arneson have come up with the free-rules role-playing concept, and would someone other than Gygax have been able to turn that into a published game? I think the answers to that are, respectively, maybe and probably. |

|

|

|

Post by increment on May 2, 2017 8:25:14 GMT -6

would someone other than Arneson have come up with the free-rules role-playing concept Can someone who has read the book help me understand what Arneson is supposed to have come up with here? I gather it is presented as something unprecedented in the history of game design, but I've been having some trouble seeing how it is different from the free Kriegsspiel principles of the 1870s that trickled down to the 1970s through intermediaries like Totten, Korns, Bath, the Midgard folks, etc. There was a lot of this going around. I mean, everyone sliced it a little differently, and small differences can yield big impacts, but it seems like something that is hard to sell as a bolt out of the blue. As for could anyone other than Gygax have done it, I think the problem isn't the "could" but the "would." Not a lot of people were publishing rules like Chainmail at the time, at least not in America, and it is a serious question whether anyone not in that Guidon Games circle would have ever taken on a project like this as a commercial release. |

|

|

|

Post by Stormcrow on May 2, 2017 11:23:11 GMT -6

would someone other than Arneson have come up with the free-rules role-playing concept Can someone who has read the book help me understand what Arneson is supposed to have come up with here? I gather it is presented as something unprecedented in the history of game design, but I've been having some trouble seeing how it is different from the free Kriegsspiel principles of the 1870s that trickled down to the 1970s through intermediaries like Totten, Korns, Bath, the Midgard folks, etc. There was a lot of this going around. I mean, everyone sliced it a little differently, and small differences can yield big impacts, but it seems like something that is hard to sell as a bolt out of the blue. I have NOT read Rob's book, but I gather that the Arnesonian genius being pointed to is not just Free Kriegsspiel's principle of the umpire making rulings based on his military experience, it is the ever-evolving system of rules and ideas that get used to support Free Kriegsspiel–style decisions. So whereas in FK a player could come up with orders that have never been tried before and the umpire would make a decision on its outcome based on his experience, in Blackmoor if a player tried something novel Dave would (apparently) spontaneously invent a whole new system to account for it—in the moment the player asked for it—and this system would itself not be set in stone but would be subject to future changes. This framework of ever-changing corpus of rules or systems is Blackmoor, not the sum of the rules in it at any given moment. D&D, I think he accuses, by presenting a mere snapshot of a campaign's possible rules and not focusing on the evolving nature of campaigning and on designing new rules and systems, fails to transmit the Arnesonian genius concept to people who weren't there to experience it. Now I think the book is overpriced and, being on a budget, and hearing how understanding it requires understanding systems theory and parsing Rob's nigh-impenetrable style, I can't justify buying it, so I can only go on what other people are saying about it. I too would like to have someone who is not Rob lay out what the genius principle is in a simple way, to verify whether I've got it right above. |

|

|

|

Post by Stormcrow on May 2, 2017 11:31:15 GMT -6

As for could anyone other than Gygax have done it, I think the problem isn't the "could" but the "would." Not a lot of people were publishing rules like Chainmail at the time, at least not in America, and it is a serious question whether anyone not in that Guidon Games circle would have ever taken on a project like this as a commercial release. Right, but in our alternate history where Gygax didn't get friendly with Arneson and learn about Blackmoor, we can't predict whether someone else with publishing ambition might eventually have taken the spot that Gygax did. Maybe not at the time Gygax did, but eventually. |

|

|

|

Post by cadriel on May 2, 2017 12:51:07 GMT -6

Can someone who has read the book help me understand what Arneson is supposed to have come up with here? I gather it is presented as something unprecedented in the history of game design, but I've been having some trouble seeing how it is different from the free Kriegsspiel principles of the 1870s that trickled down to the 1970s through intermediaries like Totten, Korns, Bath, the Midgard folks, etc. There was a lot of this going around. I mean, everyone sliced it a little differently, and small differences can yield big impacts, but it seems like something that is hard to sell as a bolt out of the blue. I don't know that I could, despite having read the book. Rob listed 26 separate things that Dave Arneson did that are "leaps" in system design away from what previously existed on the market, but he wrote them all in the language of systems theory so it's literally a list of things like "Ongoing applied design and design theory in real-time; embedded extensions of the design processing brought to bear in designing the game." If you'd be interested in reviewing it, PM me. I'd be willing to send you my copy gratis as long as you'd write a review on your blog. |

|

|

|

Post by robertsconley on May 2, 2017 13:28:25 GMT -6

Can someone who has read the book help me understand what Arneson is supposed to have come up with here? I gather it is presented as something unprecedented in the history of game design, but I've been having some trouble seeing how it is different from the free Kriegsspiel principles of the 1870s that trickled down to the 1970s through intermediaries like Totten, Korns, Bath, the Midgard folks, etc. There was a lot of this going around. I mean, everyone sliced it a little differently, and small differences can yield big impacts, but it seems like something that is hard to sell as a bolt out of the blue. Well from reading your work, the various anecdotes by others, Rob Kuntz's book, Hawk & Moor, etc; what unique is combination of elements Dave Arneson used in his Blackmoor campaign. Thanks to his temperament, skill, and interest he stuck at it long enough that the idea matured to the point that during that fateful game in Lake Geneva Gary Gygax could see what could be done with Dave's ideas. While Gary Gygax is a skilled game designer the most important thing he added into the mix was the ability to distill, and playtest what Dave did into a form that could published and for other people to learn about. That combination and the fact he made it work over the long haul is the "bolt out of the blue" so to speak. |

|

|

|

Post by robertsconley on May 2, 2017 13:39:04 GMT -6

As for could anyone other than Gygax have done it, I think the problem isn't the "could" but the "would." Not a lot of people were publishing rules like Chainmail at the time, at least not in America, and it is a serious question whether anyone not in that Guidon Games circle would have ever taken on a project like this as a commercial release. Right, but in our alternate history where Gygax didn't get friendly with Arneson and learn about Blackmoor, we can't predict whether someone else with publishing ambition might eventually have taken the spot that Gygax did. Maybe not at the time Gygax did, but eventually. Being a fan of alternate history and from time time writing a bit of my own and helping others with their timeline over on the Alternate History forum, to come up with a plausible alternative you have to break it down into its various elements and come up with a new series of events that results in the first published tabletop roleplaying games. My opinion that without somebody like Gygax, Dave would continued to be a awesome referee and gamer without a lot of published credit to his name. If you wanted to figure out an alternative path a good question is to look at earlier games he authored like Don't Give Up the Ship and see who he could have worked with. And that person would provide the push and organization for Dave to turn the Blackmoor Campaign into a something that was published. For my part I wrote a two part story about an alternative path for the development of RPGs. It based around the idea that RPGs (or Adventure Games as they are called in the ATL) developed out of a book written as aid for writing Science Fiction back in the 40s. odd74.proboards.com/thread/7798/travelling-alternate-vision-rpgs |

|

|

|

Post by increment on May 2, 2017 14:06:14 GMT -6

Well from reading your work, the various anecdotes by others, Rob Kuntz's book, Hawk & Moor, etc; what unique is combination of elements Dave Arneson used in his Blackmoor campaign. Thanks to his temperament, skill, and interest he stuck at it long enough that the idea matured to the point that during that fateful game in Lake Geneva Gary Gygax could see what could be done with Dave's ideas. While Gary Gygax is a skilled game designer the most important thing he added into the mix was the ability to distill, and playtest what Dave did into a form that could published and for other people to learn about. That combination and the fact he made it work over the long haul is the "bolt out of the blue" so to speak. I don't think that's what Rob is getting at, from the way he talks about it. |

|

|

|

Post by increment on May 2, 2017 14:31:51 GMT -6

... Arnesonian genius being pointed to is not just Free Kriegsspiel's principle of the umpire making rulings based on his military experience, it is the ever-evolving system of rules and ideas that get used to support Free Kriegsspiel–style decisions. I didn't literally mean refereeing from your experience as a member of the Prussian General Staff, I meant the way that people in the 1970s interpreted the "anything can be attempted" of Totten, and so on. Every miniature wargamer was a rules hacker, and every campaign had a unique and evolving set of rules for it, and when "anything can be attempted" your referee needs to be able to adapt to anything. |

|

|

|

Post by derv on May 2, 2017 15:21:47 GMT -6

But, I am inclined to think about Gary's contribution in a different light. The question I come to is, would D&D have been a marketable success without him? I'm inclined to say no, Arneson as true genius or not. The two questions are, would someone other than Arneson have come up with the free-rules role-playing concept, and would someone other than Gygax have been able to turn that into a published game? I think the answers to that are, respectively, maybe and probably. This is really just mental gymnastics on my part. But, as I framed the question is as I meant it. I am not as concerned about mysterious others who might have. The reality is that Guidon chose not to publish D&D and other major producers would have had difficulty embracing it, if not out right rejecting it. Gygax was the person who took Dave's concepts and pushed them into a commercial reality without an inkling of a guarantee that it would succeed. I say this as one who is not enamored by personalities. Or, in other words, I'm not a fan boy. But, I do believe that the commercial success of D&D is owed to Gygax's vision and work effort. Consider the more limited response to the JG FFC or Arneson's Adventures in Fantasy. |

|

|

|

Post by derv on May 2, 2017 15:40:07 GMT -6

Can someone who has read the book help me understand what Arneson is supposed to have come up with here? At it's core, I believe Kuntz is saying that he created a framework (architecture), not thought of before, that is not dependent upon structured rules (sub-systems) or data, yet is still complete as a system. The essence of the original concept is found in the architecture of the game. The sub-systems are inconsequential and/or mutable and do not truly define Arneson's creative leap, an ever changing and adaptive design. Best I can do  |

|

|

|

Post by howandwhy99 on May 2, 2017 15:51:49 GMT -6

Are there any examples of the generative mechanics used by Arneson in the text? Or the system processes he used, embedded or not? Maybe someone could unpack the jargon he is using if it is author defined philosophy?

Also, is there any mention of what gaming is particularly? And what roleplaying is too? Or why the necessity of the rules being unknown to the players?

|

|

|

|

Post by robertsconley on May 2, 2017 19:15:25 GMT -6

Well from reading your work, the various anecdotes by others, Rob Kuntz's book, Hawk & Moor, etc; what unique is combination of elements Dave Arneson used in his Blackmoor campaign. Thanks to his temperament, skill, and interest he stuck at it long enough that the idea matured to the point that during that fateful game in Lake Geneva Gary Gygax could see what could be done with Dave's ideas. While Gary Gygax is a skilled game designer the most important thing he added into the mix was the ability to distill, and playtest what Dave did into a form that could published and for other people to learn about. That combination and the fact he made it work over the long haul is the "bolt out of the blue" so to speak. I don't think that's what Rob is getting at, from the way he talks about it. Well Rob said he agreed with this statement in this post over on Murk Hill. Reading that I am not sure what his argument is other than he antagonistic towards commercial publication which of course I am on. |

|

|

|

Post by derv on May 3, 2017 14:43:24 GMT -6

Well Rob said he agreed with this statement in this post over on Murk Hill. Reading that I am not sure what his argument is other than he antagonistic towards commercial publication which of course I am on. Okay, it seems most of the conversation on this subject is happening over there. Thank you for pointing it out. I guess since I consider myself primarily a squatter on this forum who is not easily moved to other fora, I'll likely be having a somewhat limited conversation here. Possibly a conversation with myself  Good to know. I'll take some time to read through the thread, never the less. |

|

|

|

Post by derv on May 3, 2017 14:50:21 GMT -6

Are there any examples of the generative mechanics used by Arneson in the text? Or the system processes he used, embedded or not? No, not specifically. Some is language used in System Thinking and Design. Other is certainly author created to define concepts not otherwise accounted for through those studies. No, that is not truly the focus of the text. |

|

|

|

Post by howandwhy99 on May 4, 2017 8:47:38 GMT -6

I feel like I'm playing a guessing game. Is the true genius about something never before seen in system architecture or some specific mechanic related to system design? Or is it a new quality attribute for systems? All of which are fun to link to, because they give big long lists, but don't know if we are any closer to clarifying the breakthrough. If it is simply the idea of an open system, what's the fuss as that has been around for some time? As an aside, there appears to be a drive to common consensus for system architecture languages, which should be a plus for finding common ground with this new understanding. |

|

Deleted

Deleted Member

Posts: 0

|

Post by Deleted on May 4, 2017 15:46:14 GMT -6

Well Rob said he agreed with this statement in this post over on Murk Hill. Reading that I am not sure what his argument is other than he antagonistic towards commercial publication which of course I am on. Okay, it seems most of the conversation on this subject is happening over there. Thank you for pointing it out. I guess since I consider myself primarily a squatter on this forum who is not easily moved to other fora, I'll likely be having a somewhat limited conversation here. Possibly a conversation with myself  Good to know. I'll take some time to read through the thread, never the less. You are always welcome to be a squatter over there too!   |

|

|

|

Post by derv on May 4, 2017 15:59:27 GMT -6

howandwhy99 The true genius is "something never before seen in system architecture" as expressed in system design language. I personally believe language, as it is used, is purposeful, whether consciously or unconsciously, both spoken and written. Words in context communicate certain ideas. In other context they can communicate something else entirely. What I'm saying may sounds like, duh. But a problem still exists when two people can be saying the exact same thing and still not be at a point of agreement, even when they are speaking the same native language. The problem is that we do not all have or use the same lexicon for that language. We mean different things when using the same words in the same context of a sentence. So, on one level, I appreciate that Rob is trying to establish the ground of a common lexicon through System Thinking. Yet, I don't think there are enough in the hobby who care to learn that language. If others are not going to embrace the means through which he is trying to prove his point, whose minds will be changed through his arguments? For instance, there seems to be some on-again-off-again discussion on PD's forum that attempts to make a correlation with what Rob means by Arneson's concept and the terms "campaign" and "setting", as if what Rob is really saying is embodied in those terms. But, it isn't because those terms have specific meanings both now and in the past that aren't even necessarily the same. People mean a number of different things with these terms in the gaming community. More importantly, in System Speak they could be considered sub-systems that have little impact on the architecture of the game and Rob is talking about system architecture when he speaks of Arneson's concept. On another subject, I haven't heard anyone else say it, but I'd feel remiss if I didn't at least mention how I love the cover pic for Rob's book.

|

|

|

|

Post by derv on May 4, 2017 16:01:16 GMT -6

You are always welcome to be a squatter over there too!   You are always the gentleman, PD. Thank you. |

|

|

|

Post by derv on May 5, 2017 5:33:16 GMT -6

I'm skipping out the door after reading some more over at Murkhill. If increment stops by, I'd like to point to the statements found in my OP and suggest that he considers the rules of causality, applicable to a range of science and philosophy, when furthering his arguments, if I could be so bold. |

|

|

|

Post by increment on May 5, 2017 9:23:32 GMT -6

I'm skipping out the door after reading some more over at Murkhill. If increment stops by, I'd like to point to the statements found in my OP and suggest that he considers the rules of causality, applicable to a range of science and philosophy, when furthering his arguments, if I could be so bold. I did find your notes in the OP useful, derv, and from the sense I'm getting, I agree that Rob is trying to build as you say "transcendent" models of these systems and use a theoretical apparatus to demonstrate relationships between those systems rather than arguing from causal chains of influence that unfold over time. Most of what I'm questioning is just the data that was used to build the models, since if I don't agree with the data, I probably wouldn't agree with the comparison. The apparent lack of an impartial method for deciding on a few critical data points (like, what really is Chainmail?) makes me nervous. I don't happen to be the sort of history guy who views linear causation as the main way that influence spreads. When I am being pretentious and talking to academics about this, I tend to say that I think concepts like these in the evolution of games are transmitted rhizomatically, rather than arborescently - basically, that I think ideas crop up in similar and related permutations simultaneously in lots of places, and that it is largely contingent factors that end up promoting some ideas to success instead of others. It also means I don't tend to think any one guy tends to have invented anything, but instead I focus on the history of the connections and relationships between tons of influences, ideas, and people that creates broader cultural advances. Though I do agree there is an economic dimension to this as well. Agreed about Edison, I suspect the reason we associate him with this advance was not so much for inventing a lightbulb, but for seeding an industry built upon power delivery for which a certain type of light bulb happened to be the "killer app" as we would say today. |

|

|

|

Post by howandwhy99 on May 5, 2017 9:49:18 GMT -6

I see you jumped boards, but I don't need a response. So, on one level, I appreciate that Rob is trying to establish the ground of a common lexicon through System Thinking. Yet, I don't think there are enough in the hobby who care to learn that language. If others are not going to embrace the means through which he is trying to prove his point, whose minds will be changed through his arguments? But D&D is designed to be a system, IOW a game - a strategic enterprise where we as designers painstakingly balance the game along the likes of competitive wargames. Now D&D is different, it's not competitive for one, but the big point here is the concepts used to talk about D&D for its first decades are utterly absent in the game design community today. I see that as a tragic loss leading to a profound decline in understanding, not just of D&D and what D&D roleplaying is, but of game design in general. My suspicion was DATG was an attempt to join the storytelling community of game theory (aka narrative theory) due to its triumphant stance and the shaming of other ways of thinking. But Rob's focus on system theory makes me hope otherwise. My new suspicion is now we are sweeping under the rug "2000 years of game design" (where are the cultural artifacts of that?) for some after the fact theory formulated decades later. Histories written outside of their times are dubious like that. I suspect what we need is actual game theory, the 2000 years of design practices and jargon that led to D&D. To me, the Great Genius of Dave Arneson is he was the first to turn gaming from war scenarios to gaming everything imaginable. Not group narrative making, but the players system mastering everything they could coherently imagine because everything they could convey to the referee could be transformed from drawings and text into game content (mathematical objects and environments following systemic operations). Or more simply, Arneson was the first to capably attempt to make everything imaginable into a game and still successfully gameable. |

|

|

|

Post by cadriel on May 5, 2017 14:28:14 GMT -6

|

|

|

|

Post by derv on May 5, 2017 15:36:30 GMT -6

Let me see if I can throw some thoughts together. Kuntz's primary argument, as I see it, is 1. Arneson's Concept, his true genius, is found in the system architecture. 2. That architecture is a holistic system as it stands, devoid of any sub-systems (this includes Chainmail and any Chainmailisms). 3. The Arenson Concept is also found in the 3 LBB's. So, the questions might be 1. Is the Arneson Concept a holistic system? 2. Is the sub-systems associated with Chainmail inconsequential? 3. Does the Arenson Concept reside in the 3 LBB's? These are questions that are verifiable and/or falsifiable because we actually have the physical text of the 3 LBB's (not to mention the Dalluhn Manuscript). Hypothetically, we can replicate the LG experience, so to speak. How? Four experiments with two models could be ran to support or disprove Kuntz's theory. Get a sampling of people who have no experience with RPG's- preferably, they do not even know what the term means. Break them up into four test groups. First group should be of various ages. Give them a copy of the 3 LBB's and tell them to play the game. Second group should be of various ages. Give them a copy of the 3 LBB's stripped of all Chainmailism's (lightly edited for readability). This is a reductionist approach and should still contain the architecture of Arneson's Concept. Have them play the game. Third and fourth groups would contain only young children (possibly ten or under). Have these group's perform the same experiments as the first two. These two control groups will establish whether such play is intrinsic or innate among children. If Arneson's concept is evident in the 3 LBB's seperate from the sub-systems, it will be self evident. If Arneson's Concept is a holistic system, it will be playable. If such play is intrinsic, then a child should be able to apply Arneson's Concept. I might be biting off a little more than should be attempted, but heh  |

|